A Brooklyn high school’s new program hopes to train tomorrow’s educators

5 min read

Veteran Brooklyn high school leader Connie Hamilton noticed something over the years: Many of her former students wanted to work in the schools she ran.

“Tons of them wanted jobs from us. They wanted to be teachers and paras and school aides and guidance counselors,” said Hamilton, who retired earlier this school year as principal of John Dewey High School, and had previously headed two schools at once — Kingsborough Early College School and Dewey. “When kids love their schools and love their teachers, and teachers are modeling great work, kids want to be teachers.”

Hamilton ended up mentoring and hiring some former students, but she wanted to create a more sustainable pipeline.

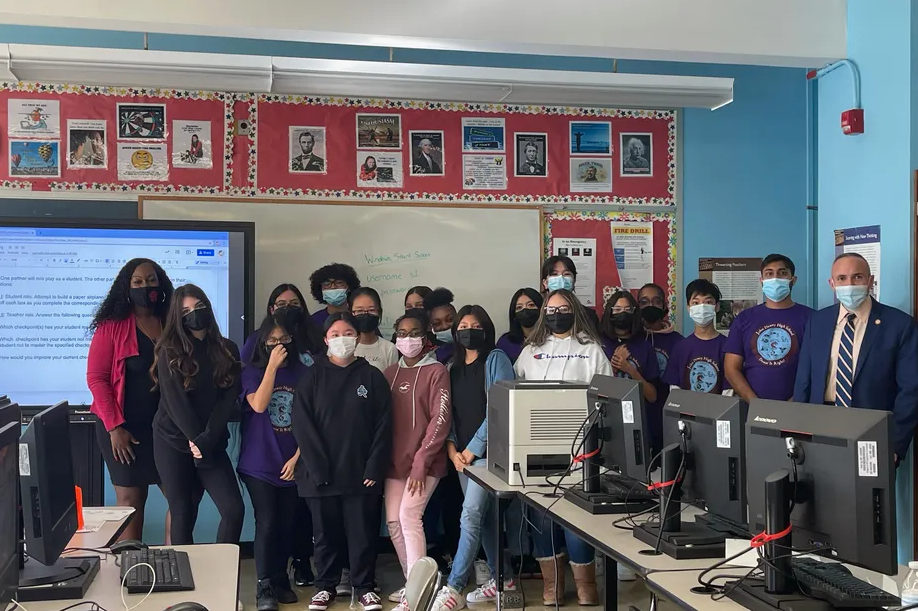

A longtime proponent of career-focused education, she dreamed of opening a teaching academy for high school students to help build a pipeline of Brooklyn educators and spent years trying to make it happen. Her vision finally bore fruit in September when Dewey welcomed 34 students into its inaugural teaching and learning academy class.

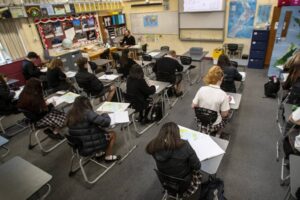

In addition to taking high school courses in pedagogy and social-emotional support for teaching children, students also have the opportunity to earn college credits through CUNY to kick start careers in education. Eventually, a middle school is expected to rise next to the campus where the high schoolers will be able to student teach.

The program’s launch comes at a crucial time. State officials have grown increasingly concerned about a looming teacher shortage and are also looking for ways to diversify the education workforce. Enrollment in state teaching programs has decreased by more than half since 2009, and about a third of current teachers are projected to retire in the next five years, Gov. Kathy Hochul cited when announcing recent proposals to attract more New Yorkers into education.

The journey to create Dewey’s program was long and winding, and ultimately got off the ground because someone else had a similar idea at the same time as Hamilton: then-Brooklyn City Council member Mark Treyger. The former teacher and head of City Council’s education committee helped secure funding for the collaboration with CUNY as well as the money to build a 550-seat middle school that will serve as a feeder school for Dewey and a lab for the future student teachers.

“I think it’s a game changer for us. We’re recruiting the best and brightest in our own neighborhood,” said Treyger, who now works as the education department’s director of intergovernmental affairs. “The state of our teacher workforce is something that concerned me even before the pandemic. People are feeling burned out. They don’t feel respected. They feel undervalued, and it’s been exacerbated by the pandemic.”

He was also concerned about the perennial shortage of bilingual educators, particularly in special education. He hopes the program might encourage some of the school’s multilingual students to go into the teaching profession — and ease the financial burden by enabling the students to earn college credits during high school.

“It’s an equity issue,” he said. “Here, we might be inspiring folks to go deeper into the profession, or they feel like it’s not for me, and don’t have to spend the money for it in college.”

The teaching program has not yet been certified as an early college program or a career and technical education, or CTE, program, but the school is hopeful it may be in the future, school leaders explained.

For now, the students in Dewey’s teaching program are able to take college courses taught by Kingsborough Community College instructors at the high school and earn college credit. First semester, they took Spanish, and now they’re taking a computer course. The goal is to eventually have the students graduate with a high school diploma and an associate degree in education that will enable them to be paraprofessionals while they also attend Brooklyn College to work toward their teaching credentials.

When Hamilton took the helm of Dewey about seven years ago following a grade fixing scandal, she saw students “falling through the cracks,” so she tried to make the school “more personal,” creating several career-focused tracks, including culinary art and pre-med. She believed the programs would give students something to get excited about.

It seems to have worked: Enrollment, which had fallen to 1,900 when she took over, she said, is now about 2,300.

Just as Dewey has seized on the CTE model, the field of career and technical education seems to be having a resurgence, with state education leaders looking to increase funding for such programs by $65 million. Mayor Eric Adams and Chancellor David Banks have also voiced support for career-focused programs.

Ninth grader Eve Smith wakes up at 5:50 a.m. each morning to make the 2-hour commute from her home in Jamaica, Queens, to the Gravesend, Brooklyn campus to be part of the teaching academy.

“Everyone around me always told me I’d be a great teacher,” said the 14-year-old, who previously tutored her peers and younger children. “I feel like the way that students view their teachers is completely different than the way teachers view their students. As a teacher, I want to clear that up… I want to be a teacher that the students can count on. If they need help, I want to be there for them. They don’t have to be afraid if they have questions.”

Smith hopes she’ll be able to start working earlier than some of her peers since she’s already racking up college credits and may only have to complete two years of college after high school.

Dewey’s new principal Heather Adelle is projecting to double the number of incoming ninth graders in the program next year to 68, and is optimistic that the program’s graduates will become the teachers of tomorrow.

“We’re really excited to have these pipelines that we’re able to build here in South Brooklyn,” she said, “to foster a love for education, and for students to understand there’s limitless possibilities for their future.”

This article was originally posted on A Brooklyn high school’s new program hopes to train tomorrow’s educators