Charter schools turn 30 this year. Here’s what I learned when I asked alumni about their experiences.

4 min read

What former students had to say about diversity, discipline, and what still needs to change.

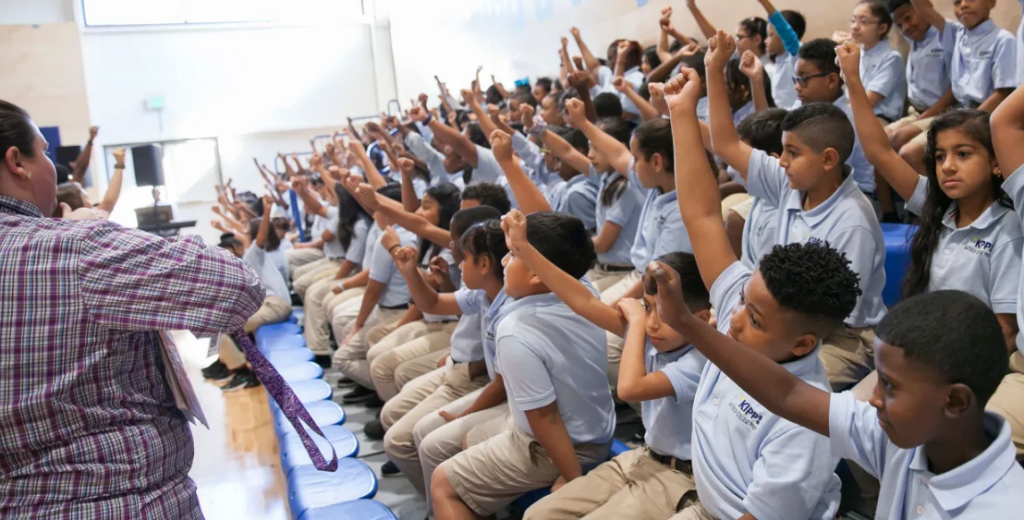

Growing up in Memphis, I attended a district elementary school before my family decided to enroll me in a charter middle school, KIPP Memphis. My neighborhood school was convenient and a family tradition, but it was considered a “poor performing” school, with lower than average test scores and graduation rates. My family decided that they wanted a better option for me, even if it meant transitioning from the school within walking distance to the school 35 minutes away by car.

My experience sometimes mirrors the national discourse around charters: I was at a school founded by non-Black outsiders with a student body mostly composed of Black students, for one. Sometimes it does not: Most of my teachers were Black and instilled the importance of my culture in me.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the creation of the first charter school, and the public debate around charters has only grown more intense. For three decades, parents, educators, school administrators, and policymakers have driven conversations that shaped everything from whether charters should exist to how charters discipline their students. But rarely have these decisions included the perspectives of those who have been the most impacted by the rise of charters: their students and alumni.

We now have a generation of charter school alumni whose experiences as charter school students can be used to inform improvements to charter school programs and charter school policy, and educational policy more broadly. As schools and districts navigate a path forward beyond the pandemic, we are an untapped resource.

I launched a national public survey earlier this year alongside my colleagues at Next100, a start-up think tank, aiming to fill a hole in our public understanding of charters and to gauge alumni priorities for improving charters moving forward. Some individual charter schools and networks survey their alums, but broad insights on charter experience across networks, schools, and geography that can inform both policy and practice are limited.

Some of what I heard surprised me, and much of what I heard mirrored my own perspective. Of more than 300 respondents, two in three said they had a mostly positive experience attending their charter school. Similar to most families, they were most likely to choose the charter they attended because of the perceived differences in quality, discipline, and curriculum from their district option.

But the charter alums I surveyed also pointed to key areas where charters were falling short — and offered ideas for how these schools could improve for the next generation of students.

For instance, less than half of charter alums believe discipline practices at their school were fair. Many raised concerns about the lack of diversity among their teachers. Given that the pandemic has exacerbated racial inequity in the classroom, these findings should encourage schools to prioritize improving discipline practices so that they are culturally competent, fair, and restorative. Alums also pointed out that charters could do more to recruit educators who reflect the diversity of the students they teach and invest in cultural competence training for all teachers regardless of their race or ethnicity.

It is important to remember that charter school alumni are not a monolith. Their experiences are as diverse as they are, spanning large charter networks and small independent schools, big cities to small towns, and at schools predominantly filled with people of color or not. That’s why it is important for leaders to include many alumni voices in decision-making groups at all levels of charter governance — for individual schools, regional networks, and state and federal policymaking.

For now, key voices have been drowned out. Charter alums are itching to tell our stories, and to share our experiences and recommendations for change, but our perspectives are not as valued as national advocacy organizations and policy experts, who have likely not experienced charter schools as we have.

In 2017, I saw my own network take the first step as I and other alumni from the KIPP network began to lead delegations to national civil rights conferences. We began to speak on the racial equity work that needed to be done both internally and in our communities as a whole. The experience offered proof of the positive impact alumni voice can have.

If charter schools want their next 30 years to be better than their last, I hope they will make sure that their alumni help chart their path forward.

This article was originally posted on Charter schools turn 30 this year. Here’s what I learned when I asked alumni about their experiences.