More Tennesseans of color walk away from teaching profession if they fail first licensure test, report shows

4 min read

About a fourth of Tennessee elementary school teacher candidates who fail their licensure test on their first attempt don’t try again, with an even higher “walkaway rate” for aspiring teachers of color, says national data released Wednesday.

For Tennesseans of color who failed their first exam, about a third didn’t retest for licensure, according to a report by the National Council on Teacher Quality, or NCTQ.

First-time passage rates also varied significantly among the state’s nearly 40 teacher training programs — from 7% at LeMoyne-Owen College to 100% at Vanderbilt University.

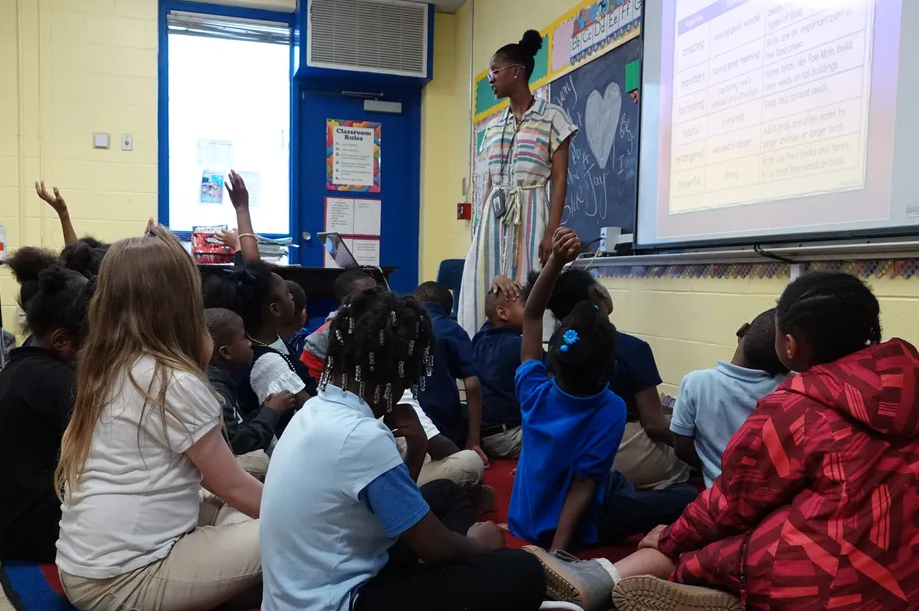

The data, which NCTQ officials say is being released for the first time, offers important insights for Tennessee in its push to replenish, strengthen, and diversify its workforce of 61,000-plus public school teachers — and to have an effective teacher in every classroom.

The analysis focuses on elementary school teacher candidates between 2015 and 2018, when Tennessee required its test takers to pass two Praxis exams to obtain licensure. One test generates an overall score on content knowledge, which is defined as the minimal knowledge needed to teach a subject.

In 2019, the state switched to a single Praxis exam that generates individual scores on content knowledge in math, science, social studies, and English language arts. Candidates may retake the subsections they fail but must pass all to obtain licensure.

“We are pleased that Tennessee has moved to a more rigorous licensure assessment that requires passing each content area, but I think this data is still relevant,” said Hannah Putman, the council’s managing director of research, who oversaw the national report. “It’s likely that institutions that struggled on the two previous tests are continuing to struggle on the new test, so the trends are worth looking at.”

The report shows an average of 93% of Tennessee candidates passed the state’s previous test on pedagogy on the first try, while only 67% passed their initial content knowledge test.

More importantly, the data gives a glimpse into each institution’s level of encouragement and support for teacher candidates retaking a failed test, as well as the level persistence on the part of test takers.

“I can see why students might walk away when they fail the Praxis [test], especially those who are minorities,” said Nicholas Clifton, a Black college student in the process of taking his licensure exam to teach elementary school in Tennessee.

Growing up in rural Georgia, Clifton was an honor student and basketball star but struggled academically once he reached Maryville College, near Knoxville, where he’s entering his senior year as a student-athlete.

“I didn’t have the proper preparation to write an essay or cite references from a website. I was never taught that,” said Clifton. “Then when I found out about the Praxis, I said, ‘What’s that?’”

Clifton had to take several Praxis screener tests to pursue his elementary education degree at Maryville College, and failed multiple times before passing. He’ll have to pass more exams to get licensed but feels better prepared because of his Praxis testing experience and the support he’s received from his professors.

“When you have to pay to take these tests and see how much teachers get paid, you wonder if it’s worth it,” he said. “But I know we need male educators of color. When I was growing up, I had none.”

Experiences like Clifton’s are common and must be considered and addressed by teacher training programs, said Diarese George, a former teacher who is executive director of the Tennessee Educators of Color Alliance.

“If you’re a product of K-12 inequity, you’re always playing catchup,” George said. “For folks who want to be a teacher, there are usually things on your licensure test that you probably never learned along the way.”

The new information in NCTQ’s report, which covers 38 states and the District of Columbia, has been highly anticipated by Tennessee policy officials, who have worked closely with the state’s teacher training programs since a 2016 report said most weren’t adequately preparing teachers for the classroom.

The State Board of Education releases an annual report card grading the training programs on criteria such as completion rates, racial diversity, placement and retention in Tennessee public schools, and whether they produce teachers for high-need areas such as special education and secondary math and science.

Earlier this year, the board approved a new policy requiring Tennessee school districts to set goals and strategies to get more teachers of color in front of students.

Board spokeswoman Elizabeth Tullos said staff are anxious to dig into the new NCTQ data, which she said “will be invaluable as we set policy goals for the next year.”

George, who taught for five years in Clarksville before starting the Educators of Color Alliance, is glad to see any data or policies that help teacher training programs address inequities in education.

“To eliminate the gaps, we have to understand what made the gaps in the first place and then include that in the [teacher] preparation experience,” he said.

“If a student has the heart and will to become a teacher and a love for kids, there are ways to support them and help them get there, even if they were behind when they got to college.”

This article was originally posted on More Tennesseans of color walk away from teaching profession if they fail first licensure test, report shows