This Indiana educator finds inspiration on TikTok and teaches skills that can’t be measured on tests

6 min read

In the spring of 2020, when schools closed due to the pandemic, Indiana teacher Kelsey Pavelka heard from families that their students were struggling — not just with classwork but from the mental toll of isolation.

Inspired by an idea from TikTok, Pavelka constructed a plastic barrier at her front door with sleeves on either side so she could hug her second grade dual-language students.

“I had super strong relationships with those families, and we’d just been through a lot together over the years,” said Pavelka, who teaches at West View Elementary in Muncie. “When I saw it on TikTok, I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, I think this is a safe way I could do something crazy, and the kids would love it.’”

Pavelka created the hug station because she believes that most important lessons and interactions with students aren’t governed by state standards, and they aren’t skills a test can measure. She recently spoke with Chalkbeat about how her classroom changed during COVID, how she addressed the Black Lives Matter protests with her students, and what she hopes education will look like after the pandemic.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

There wasn’t a moment for me. I didn’t major in education during my undergrad. But after college, I heard about Teach for America and I fell in love with their mission. It was during my Summer Institute as a TFA Corps Member in Las Vegas that I discovered my love of teaching. I got so much joy from being able to break down complex skills and ideas into digestible chunks for our youngest of learners.

What does a typical day look like for you now?

Our dual-language program’s goal is to have 50% of the class be native English speakers and 50% native Spanish speakers. We start in kindergarten, and 80% of the day is in Spanish while 20% of the day is in English. We grow one grade-level each year — we’re adding fourth grade in this upcoming year.

Math is a really fun class to teach in Spanish. [Math is] called the universal language: The concepts are all the same; it’s just the vocabulary they need to learn. Honestly, a lot of math vocabulary is what we call cognates — they’re similarly spelled and similarly said to their English counterparts.

The last hour of the day is an important time for me to teach concepts in English like phonics or sight words. I also use this time to help students make connections between Spanish and English so that they begin to understand how the two languages do not compete for space in their brains. Instead, they work together to create deeper connections for them.

What challenges do you face teaching dual language in first and second grades during this year?

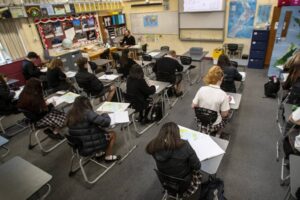

Our dual-language immersion classrooms are so collaborative that the biggest challenge has been finding new ways for students to work together without being physically close to each other.

I had been hopeful I would be able to keep table groups in a safe way, perhaps through plastic dividers, so students could still work together. But we couldn’t do that — all their desks had to be six feet apart. Every routine and procedure that I had for my classroom had to change, even passing out pencils. Six feet is a lot of feet for little hands.

We used WebEx and Zoom, where I would teach them from my desk while they were at their desks on the video call. And then they would use that to connect with each other from their own seats.

My ability to adapt and change plans at a moment’s notice were pushed and stretched in so many ways every single day this year.

How have you approached recent news events in your classroom?

One of the pillars of the dual-language immersion program is sociocultural competence. This allows us space to talk to students about diversity, equity, inclusion, and how those things relate to their experience as emergent bilingual students.

A lot of my second grade students had gone to the Black Lives Matter protests over the summer. My role in that conversation is as a facilitator: helping them understand why people hold signs and walk in the streets, what is a protest, or why have people protested in the past? It’s giving them the context for things they hear adults talking about.

Do you think education will look different after the pandemic? If so, how?

My first hope is that communities and governing bodies will acknowledge that schools are community hubs that meet far more needs than just providing students a quality education. As such community hubs, schools should be funded to reflect the invaluable asset they are to our communities.

My second hope is that we can go back to using technology as a resource and not as the primary method for delivering instruction. There’s no question that technology has given us so many opportunities to teach students who we cannot see in person during the pandemic. But I worry that decision-makers who are not in the classroom might use this moment to overcorrect and rely too heavily on technology to teach students.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your class?

I think the biggest community change that has impacted my school and my students have been the closing of major factories in our town and the lack of jobs that pay a livable wage. This gap leaves families in a cycle of poverty, and oftentimes trauma, that students carry with them into our classrooms.

Our district and our teachers dedicate hours each week to teaching social-emotional skills to address these behavioral gaps so that students know and feel that they are in a safe space at school. There are no “state standards” for that, but these are skills that teachers have to teach long before students are ready to invest their energy into the math and literature lessons the teacher has planned for them.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received, and how have you put it into practice?

I watched the Dartmouth graduation speech that Shonda Rhimes gave in 2014 over 20 times. She gave it the same year I graduated from undergrad, and it has shaped the way I view my life.

In it, she says, “Whenever you see me somewhere succeeding in one area of my life, that almost certainly means I am failing in another area of my life. … That is the tradeoff.”

I feel the exact same way about teaching. There are so many expectations placed on teachers, it’s easy to feel like you’re constantly dropping the ball on something. I have to remind myself that it is normal to focus my energy on certain areas, even when that means I’m letting other areas fall to the wayside for a bit. It’s part of the tradeoff. I don’t let myself feel guilty about it.

You have a busy job, and this is a stressful time. How do you take care of yourself when you’re not at work?

I have an amazing wife who keeps me grounded and helps me regain my focus when I get overwhelmed. We love to travel with our three kids, hang out with our friends, and I listen to a lot of podcasts!

Right now, I’m listening to “Undisclosed,” a podcast by Rabia Chaudry. They’re a group of attorneys and each season is a case of wrongful conviction. They go through all of the evidence, and I absolutely love it. In my other life, I would be an attorney.

This article was originally posted on This Indiana educator finds inspiration on TikTok and teaches skills that can’t be measured on tests